The S&P 500 rose 6.64% in the quarter ended December 31, 2017, and 21.83% percent for the full year.[1]

As we have often mentioned, we are always on the hunt for great businesses with unassailable competitive advantages and enduring pricing power. We believe these businesses are both rare and, as a result of behavioral and institutional biases that shorten investor time horizons, almost always undervalued. Once we’ve identified one of these businesses, we compare our estimate of its forward risk-adjusted rate of return to those of our existing holdings. If the return differential is not large enough to justify reducing or replacing existing holdings, then we continue to monitor the business and wait for the differential to widen enough to justify the portfolio turnover. One frequent catalyst of this widening is when the prospective investment experiences temporary problems. In these cases, even if most market participants agree that the problems are only temporary and that the stock is attractively priced, many investors nevertheless attempt to improve their long-term returns by selling the company’s stock and/or waiting to buy it at a “better” time. Unfortunately, because of the same behavioral biases that result in the consistent undervaluation of many great businesses, we believe this market-timing generally fails and leads to, on average, a larger stock price decline than the temporary problems warrant. At this point, the prospective investment benefits from, in our view, two sources of undervaluation: the great-business mispricing and the market-timing mispricing. In many cases, the combination of these two sources of undervaluation can be large enough to justify a portfolio change.

In our last letter, we discussed how fears of one type of temporary problem, macroeconomic weakness, catalyzed our decision to add CBRE Group (CBG) to our portfolio. In this letter, we discuss how another type of temporary problem, a changing competitive landscape and reduced near-term cash flow guidance, allowed us to acquire Priceline (PCLN) at what we believe was an attractive price.

Priceline

Priceline is the largest online travel agent (OTA) in the world. We believe it is a great business because 1) travel spending has favorable long-term growth tailwinds; 2) the OTA business model is excellent; 3) Priceline is the largest, most attractively-positioned OTA; and 4) Priceline’s management is the best in the industry.

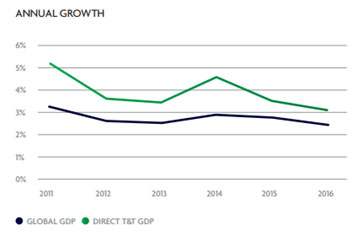

The first reason we believe Priceline is a great business is that it operates in an industry with favorable long-term growth tailwinds. In 2016, the global travel and tourism industry directly contributed $2.3 trillion (3.1%) to global GDP. Despite the industry’s size, direct travel and tourism GDP growth has handily outpaced global GDP in recent years.[2]

Furthermore, this above-GDP growth is expected to continue with travel and tourism GDP forecast to grow at a 4.0% annual rate for the next ten years to $3.5 trillion, increasing its share of global GDP to 3.5%.[3]

Priceline’s travel niche, worldwide accommodations bookings, has also grown faster than global GDP. From 2004 to 2015, bookings grew at a 3.4% annual rate, whereas global GDP only achieved a 2.8% annual growth rate over the same period.[4] Just like general travel spending, we believe worldwide accommodations bookings will continue to grow at rates equal to or faster than GDP over time. The main reason for our confidence in this growth is travel’s ability to enhance our social status and wealth.

As a result of innovation, the real price of most goods deflates over time. The average global citizen spends less on energy and food as a percentage of GDP than his or her ancestors did 100 years ago. However, some categories of goods maintain or even grow their share of GDP over time. In general, we believe these categories derive their resiliency from their social nature. They are categories that allow consumers to reliably enhance their desirability as mates or business partners. For instance, luxury goods advertise high status and tribal affiliation. Prime real estate advertises high status as well, but it also enables convenient collaboration and trade with a dense network of customers, suppliers, and partners. Travel is similarly multifaceted. It serves as conspicuous consumption and also facilitates collaboration, innovation, and wealth creation by providing opportunities for the in-person interaction that’s crucial to sustaining and deepening business and personal relationships.[5] Moreover, travel exposes individuals and groups to novel experiences and environments, which can enhance creativity, prompt new discoveries, and spark innovation.[6]

The second reason we believe Priceline is a great business is that the OTA business model is excellent. OTAs are two-sided networks that connect buyers and sellers of travel services. As such, the more hotel, airline, and rental car partners an OTA has, the more valuable it is to customers because it saves them time and money by more efficiently filtering travel options according to these customers’ wishes. In turn, the more customers the OTA has, the more valuable it is to its travel partners. As with most network-driven business models, this positive feedback loop supercharged the growth of a few early entrants, ultimately resulting in an oligopolistic industry structure of established players whose large and deep user bases make it difficult for new entrants to compete. In addition to its strong barriers to entry, the OTA business model is attractive because of its substantial customer penetration opportunities. Even today, despite rapid historical growth, only 40% of global hotel bookings and 45% to 55% of airline reservations are made online.[7] As more and more customers gain access to the internet and/or become aware of the superior value proposition of online booking sites versus traditional travel agents, we believe these percentages will continue to grow.

The third reason we believe Priceline is a great business is that it is the largest, most attractively-positioned OTA. Though Priceline and its chief rival, Expedia, have roughly equivalent global market share of gross online travel bookings at around 30% each, Priceline is the largest OTA by revenue at $4.4 billion for the third quarter of 2017 versus $3.0 billion for Expedia.[8] Thus, it can invest more resources than its competitors in acquiring new customers and maximizing the lifetime value of its existing customers. By gaining and maintaining numerous small advantages in areas such as advertising, filtering speed, website functionality, and customer engagement, Priceline has further entrenched itself as the market leader. However, even though the cumulative effect of these small advantages is quite significant, Priceline’s market-leading position on the customer demand side of its network could be breached almost overnight if a competitor were willing to throw enough money at the problem. After all, many consumers have limited loyalty to any one OTA. Instead, these consumers view Google Search or the metasearch engines such as TripAdvisor and Trivago as the most effective travel provider filters and the OTAs as interchangeable booking agents, making ad impressions the main driver of these consumers’ OTA choices. This dynamic explains why OTAs spend over a third of their revenues on advertising. Moreover, while different geographic areas present different growth and wealth profiles, customer fragmentation is almost identical in each market, meaning the OTAs operating in these various markets all have roughly equivalent pricing power over their customers.

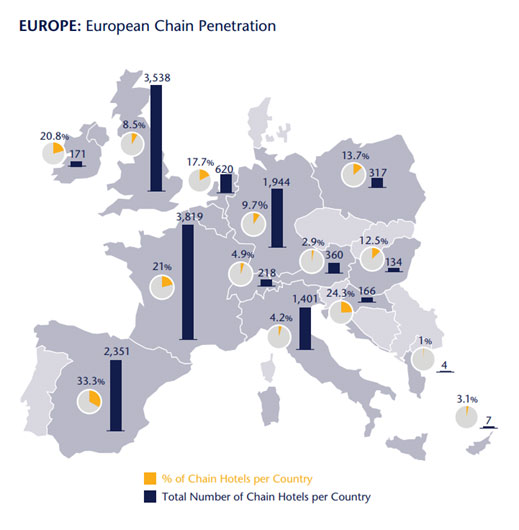

Thus, to explain the large differences in the OTA’s competitive advantages and returns on capital, we believe one must look to the supplier side of their networks. On the supplier side, fragmentation differs widely across both products and geographies. Products such as airline bookings and geographies such as the United States, where chains own roughly 70% of all hotels, are considered to have relatively low fragmentation. In these markets, the large travel accommodations suppliers find it rational to aggressively negotiate the rates the OTAs charge them and also to invest their significant advertising and technology resources in an attempt to bypass the OTAs altogether. In contrast, in more fragmented markets, suppliers’ most rational strategy is to partner with the OTAs. Priceline, mainly as a result of its global travel platform Booking.com, is the clear leader in the most fragmented product (hotels) and the most fragmented travel market (Europe). As of September 30, 2017, Priceline had approximately 700,000 traditional hotel properties on its platforms versus Expedia at only 405,000. This wider selection has translated into far more business, with customers booking 178 million room nights through Priceline in the third quarter of 2017 compared to 94 million on Expedia brands.[9] Furthermore, Booking.com’s dominance is most pronounced in Europe, where it was founded. Europe is arguably the best accommodations market in the world, with high levels of wealth, diverse cultural heritage, numerous historic cities, and, as the chart below shows, very low chain ownership.[10]

Europe’s hotel fragmentation not only increases Priceline’s value proposition to its hotel travel partners and thus its pricing power, but it also creates a very large competitive moat. Would-be competitors must engage in the extremely time-consuming task of forming literally hundreds of thousands of relationships with small boutique hotels while also designing websites and apps that offer enough benefits to switch customers to their platforms.

Therefore, in our view, Priceline’s commanding lead in global hotel bookings and its stranglehold on the uniquely attractive European market are the main reasons that Priceline’s market capitalization, at $93 billion, is four to five times that of its next largest competitors, Expedia ($20 billion) and Ctrip ($25 billion), despite Expedia’s equivalent share of gross travel bookings and Ctrip’s dominant position in fast-growing China.[11] Another contributing factor to this market capitalization gap is the fact that, outside of Europe, Priceline’s next most attractive market is Asia, where hotels ownership is also fragmented and where it has strong market share through its properties Agoda and Booking.com as well as through its partnership with and ownership interest in Ctrip.

The fourth reason we believe Priceline is a great business is its management, which we believe is the best in the industry. Priceline has demonstrated this advantage in numerous ways over the years. First, Priceline made a brilliant strategic decision in 2005 when it acquired Booking.com for $100 million. Since Booking.com accounts for the vast majority of Priceline’s profits and Priceline is worth almost $100 billion, this acquisition was clearly one of the best ever made. Second, while not yet generating another windfall like Booking.com, management has continued to acquire strategic, value-enhancing travel properties such as the Asian OTA Agoda, the restaurant booking platform OpenTable, and the metasearch engine Kayak, all of which have strengthened Priceline’s network effects in the online travel booking space. Third, instead of sticking its head in the sand, management has aggressively built up its non-hotel offerings to compete with Airbnb and its disruptive, sharing economy brethren, growing this category at a 58% annual rate to 816,000 properties as of September 30, 2017.[12] Fourth, the company is conservatively capitalized with almost $9 billion of net cash and investments on its balance sheet as of September 30, 2017. Fifth, in addition to making acquisitions, management has opportunistically used its prodigious cash flow to buy back stock. Given the long-term performance of the business and the stock, these share repurchases have been massively accretive over time. Finally, in probably the clearest example of Priceline management’s culture of long-term thinking, the company recently decided to purposefully depress short-term profits in order to protect the business’s long-term competitive advantages. In fact, as we discuss below, the stock price weakness that resulted from this decision was actually the catalyzing factor for our recent investment.

As we mentioned at the outset of this letter, we believe great businesses are generally undervalued by the market. Moreover, we believe great businesses can become even more mispriced when they experience temporary macroeconomic or operational problems. In Priceline’s case, a string of bad results from other travel players caused concern about the industry’s future profitability prospects. Then, when Priceline provided disappointing earnings guidance of its own, investor fears about the travel space seemed confirmed, and they sold aggressively. However, in our view, a closer examination of the industry suggests that Priceline was the proverbial baby being thrown out with the bathwater.

Though a simplification, it’s helpful to think of the online travel industry as comprising three levels. At the top of the travel pyramid is the search engine, which is most people’s gateway to the internet and their preferred method of filtering the vast amount of information and resources available to them there. Google, with the exception of China, essentially possesses a global monopoly of this level. Below this level are the metasearch engines such as TripAdvisor, Kayak, and Trivago. These sites aggregate reviews of vacation destinations, dining choices, accommodations, and travel activities. They began primarily as review sites that had no direct booking relationships with travel providers, and they made money by charging advertising fees in exchange for prominent placement on their site. Below the metasearch engines are the online booking sites. Priceline, Expedia, Ctrip, and the travel providers’ own websites are the main competitors at this level.

Over time, as the land grab in online travel has progressed, these three levels—the search engine (Google), the metasearch engines (TripAdvisor, etc.), and the online booking sites (Priceline, etc.)—have increasingly attempted to compete with each other. Google, with its virtually insurmountable advantage at the top of the travel food chain, has had the most success in these efforts. With continued refinements of its search algorithms and of its Google Travel platform, Google has steadily taken market share from the metasearch engines. Because of pressure from Google and the lower competitive barriers to entry at their level of the travel market, the metasearch engines have experienced shrinking margins. In order to protect their profitability, the metasearch engines have been attempting to vertically integrate into the OTA market. These efforts to take share from Priceline and Expedia have been largely ineffective, but Priceline, quite correctly, in our opinion, appears to be taking nothing for granted. The main reason for its guidance reduction was a strategic decision to pull back on advertising through the TripAdvisor, Trivago, and other metasearch engine platforms. Thus, rather than a sign of weakness, as market participants appeared to believe, Priceline’s reduced guidance was actually, in our view, a sign of a dominant company operating from a position of strength to further constrain other players’ ability to invest resources in their own competing OTA offerings. Since Priceline’s high returns and large cash flows provide no such constraints, we believe this decision is likely to enable the company to widen its already commanding lead over these upstarts.

While Priceline’s move may increase its dominance over a number of its competitors, it also increases Priceline’s reliance on Google. So, a reasonable question to ask is what’s to stop Google from taking not just the metasearch engines’ business but Priceline’s as well. To us, it seems clear that Google’s focus on dominating search has led over time to an unmatched global user base and an unrivaled ability to track and predict these users’ behavior through the information it obtains from its mobile operating system Android and apps such as Google Maps, Gmail, and, of course, Google Search. Thus, any companies whose economic models rely primarily on providing relevant online information to consumers are likely to find that Google performs these functions more efficiently and effectively over time. We believe this fact explains why metasearch engines have been losing share over time. After all, the industry category even has “search” in its name! In contrast, while Google certainly has the financial resources to take on the OTAs directly, we believe the OTA business model requires skills that are less aligned with Google’s historical strengths. In particular, it requires tremendous time and effort to successfully negotiate OTA agreements and maintain ongoing relationships with hundreds of thousands of hotels and literally millions of non-hotel lodging properties around the world.[13] Furthermore, for Google to successfully compete against the incumbent OTAs, the company would also need to develop OTA apps, websites, and other touchpoints with large enough benefits to break consumers out of their current online travel booking patterns. A famous attempt by the wireless phone companies to steal share from Mastercard and Visa provides a good historical example of the difficulty of these tasks. In 2010, AT&T Mobility, T-Mobile USA, and Verizon Wireless formed a joint venture with the unfortunate name Project ISIS to “fundamentally transform how people shop, pay, and save”—in other words, to disintermediate Mastercard and Visa.[14] However, this effort was never able to achieve much success, in no small part because of the difficulty of replicating a massively distributed network by signing up millions of merchants and attracting millions of consumers, especially when the existing system was already fairly low cost for the merchants and worked very well for consumers. In another example that’s closer to home, Amazon has unsuccessfully attempted to enter the online travel market twice, with the most recent effort, Amazon Destinations, lasting a mere six months.[15] Thus, from Google’s perspective, we believe developing new skills that are orthogonal to its main search business in an attempt to achieve uncertain profitability gains is an unappealing prospect. This course-of-action seems even more foolhardy when one considers that Google’s current travel business is already incredibly profitable. In fact, it’s arguably worth more than Priceline’s.[16] Because Google is the gateway to the internet and customers have limited loyalty to any particular booking platform, Google is able to extract a large piece of the online booking economics through the advertising dollars that the OTAs and other travel accommodations providers must spend to maintain their customer traffic.

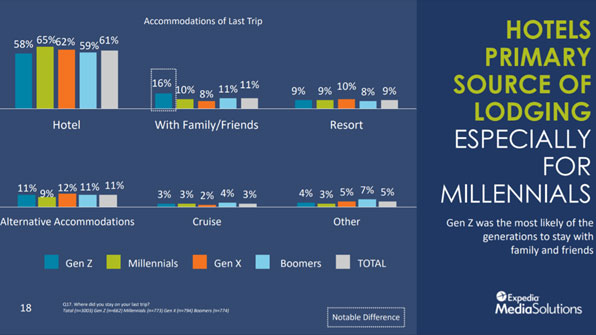

The last potential threat to Priceline comes from Airbnb. Airbnb has catalyzed a rapid increase in the supply of travel lodging through its sharing economy model, causing concern among analysts that this extra supply will increasingly pressure hotel revenues. While there’s little doubt that the sharing economy has had an impact, with one recent study of Austin, TX, quantifying the effect at 8 to 10% of hotel revenues over the last decade,[17] it is still quite unclear whether this industry disruption will turn out to be a large initial reset followed by slower future hotel market share losses or whether it’s just the beginning of a much more severe pricing deflation and market share shift. In trying to evaluate this threat, we would note a few key facts. First, hotels do provide a unique value proposition of privacy, security, and consistency when compared to alternative accommodations. Second, they often provide lower-priced access to amenities such as pools, exercise rooms, spas, and dining services since they can amortize their costs across far more customers. Third, perhaps contrary to perception, millennials appear to value these attributes about as much as prior generations, as the following 2017 survey from Expedia demonstrates.[18]

Finally, while the percentage of travelers in the United States and Europe who used Airbnb increased by 330 basis points to 25 percent during the year ended October 31, 2017, this increase pales in comparison to the 800 basis point increase last year.[19] This deceleration has occurred more quickly than many analysts expected and has caused some to question whether Airbnb is approaching saturation in these markets.19 Taken together, these facts lead us to assign a higher probability to the “large initial reset followed by slower future market share losses” scenario. In this scenario, given the large opportunity for the OTAs to take share from offline travel agents, the long-term above-GDP travel growth we expect, and Priceline’s efforts to capture some sharing economy business through its rapidly increasing non-hotel listings, we believe Priceline is still likely to grow at very attractive rates over time.

In summary, we think there’s plenty of evidence that Priceline’s competitive advantages and long-term growth potential remain quite strong. Moreover, as a result of what we believe was unwarranted selling pressure in response to Priceline’s short-term guidance reduction, we were able to purchase Priceline at a price, approximately 22x our estimate of next-twelve-months earnings and approximately 20x earnings excluding net cash and investments, that we believe significantly undervalues Priceline’s many favorable attributes.

Concluding Thoughts

While 2017 was another great year in the now almost 9-year bull market, our goal as investment managers is neither to celebrate in good times nor to despair in bad ones. Rather, our objective is to steadfastly implement an investment process that we believe will drive attractive risk-adjusted returns. Thus, day by day, we evaluate our portfolio companies’ competitive advantages as new data arises, we stress test our portfolio’s business cash flows across a range of economic environments, and we hunt for great businesses at attractive prices relative to our available alternatives, giving special attention to those industries where investors are overly focused on short-term factors. We believe our investments in CBRE Group and Priceline are the two most recent examples of the benefits of this approach.

Thank you for your trust, and please feel free to call us with any questions or concerns.

Sincerely,

The YCG Team

Disclaimer: The specific securities identified and discussed should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security nor were they selected based on profitability. Rather, this commentary is presented solely for the purpose of illustrating YCG’s investment approach. These commentaries contain our views and opinions at the time such commentaries were written and are subject to change thereafter. The securities discussed do not necessarily reflect current recommendations nor do they represent an account’s entire portfolio and in the aggregate may represent only a small percentage of an account’s portfolio holdings. These commentaries may include “forward looking statements” which may or may not be accurate in the long-term. It should not be assumed that any of the securities transactions or holdings discussed were or will prove to be profitable. S&P stands for Standard & Poors. All S&P data is provided “as is.” In no event, shall S&P, its affiliates or any S&P data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the S&P data. MSCI stands for Morgan Stanley Capital International. All MSCI data is provided “as is.” In no event, shall MSCI, its affiliates or any MSCI data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the MSCI data. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

[1] For information on the performance of our separate account composite strategies, please visit www.ycginvestments.com/performance. For information about your specific account performance, please contact us at (512) 505-2347 or email [email protected].

[2] See page 2 of https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/2017-documents/global-economic-impact-and-issues-2017.pdf.

[3] See page 1 of https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/regions-2017/world2017.pdf.

[4] See page 6 of http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/PCLN/5893537929x0x908738/9B625039-8096-48F6-8987-DD9505394BAF/Investor_Deck_FINAL.pdf as well as https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.

[5] See https://www.fastcompany.com/3051518/the-science-of-when-you-need-in-person-communication and https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1834&context=ttra.

[6] See https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/03/for-a-more-creative-brain-travel/388135/ and http://bigthink.com/insights-of-genius/why-traveling-abroad-makes-us-more-creative.

[7] See page 6 of http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/PCLN/5893537929x0x908738/9B625039-8096-48F6-8987-DD9505394BAF/Investor_Deck_FINAL.pdf and http://analysisreport.morningstar.com/stock/research?t=PCLN®ion=USA&culture=en_US.

[8] See http://analysisreport.morningstar.com/stock/research?t=PCLN®ion=USA&culture=en_US. As of Q3 2017, Expedia actually possesses a slight edge at $22.2 billion gross bookings in Q3 2017 versus Priceline at $21.8 billion.

[9] See http://analysisreport.morningstar.com/stock/research?t=PCLN®ion=USA&culture=en_US.

[10] See page 11 of http://horwathhtl.pl/files/2017/05/Horwath-HTL_European-Hotels-Chains-Report-2017.pdf for the European Chain Penetration chart shown on this page.

[11] Market capitalization statistics are as of 01/31/2018.

[12] See https://seekingalpha.com/article/4121428-priceline-group-pcln-q3-2017-results-earnings-call-transcript?part=single.

[13] As of Q3 2017, Priceline had 1.5 million total properties on its platform, and Expedia had a global lodging portfolio of over 500,000 in addition to 1.5 million online bookable listings available on its subsidiary HomeAway. While these stats appear to show relative parity between Priceline and Expedia, Priceline had 700,000 traditional hotel properties on its platform versus only 405,000 for Expedia. See Priceline and Expedia Q3 2017 earnings press releases and http://analysisreport.morningstar.com/stock/research?t=PCLN®ion=USA&culture=en_US.

[14] See https://davidschropfer.wordpress.com/2010/11/18/how-isis-could-defeat-visa/.

[15] See https://techcrunch.com/2015/10/14/amazon-shuts-down-its-hotel-booking-site-amazon-destinations/.

[16] See https://skift.com/2017/09/18/google-travel-is-worth-100-billion-even-more-than-priceline/.

[17] See http://journals.ama.org/doi/abs/10.1509/jmr.15.0204?code=amma-site&mobileUi=0&journalCode=jmkr.

[18] See https://www.hotelmanagement.net/sales-marketing/expedia-white-paper-european-traveler-habits-counters-theory-airbnb-stealing-hotel and https://www.google.com/search?q=expedia+multi+generational+travel+trends+accommodations+of+last+trip&rlz=1C1CHBF_enUS774US774&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjqo6OV-_PYAhVGC6wKHURABQAQ_AUICygC&biw=1914&bih=915#imgrc=CxP3wLecutHwnM:.

[19] See https://skift.com/2017/11/15/airbnb-growth-story-has-a-plot-twist-a-saturation-point/.