The S&P 500 Index returned 13.65% in the quarter ended March 31, 2019.[1]

In our last letter, we noted the 13.52% decline in the S&P 500 that occurred during the fourth quarter of 2018. We then discussed the pain and discomfort many people experience as a result of these types of declines. As an antidote to these emotions, which we believe cause investors to take actions that are detrimental to their financial health, we showed the long-term returns of equities around the world versus cash, short-term government bills, and long-term government bonds. While many investors consider equities to be “risk” assets and cash, bills, and bonds to be “risk-free” assets, the historical data paints a powerful picture that turns this conventional wisdom on its head, showing the wealth-generating potential of long-term equity ownership and the, in many cases, wealth-destroying potential of long-term cash, bill, and bond ownership. While we stand by this analysis and strongly believe that owning a broad index of equities is a great approach to build wealth, we think investors can do even better. At YCG, by owning a carefully-selected group of equities that we understand well, we believe we and you, our clients, have the potential to generate better risk-adjusted performance than the equity market as a whole while also experiencing less discomfort during market downturns. In this letter, we discuss the process we use to select these equities as well as the rationale behind it.

YCG Investment Strategy

In designing an investment strategy, we first had to answer the question, “What strategy gives us the best shot at earning excess returns without forcing us to take excessive risk?” In our mind, there are three types of advantages a strategy can utilize to earn excess returns: informational, analytical, and behavioral. We think informational advantages are exceedingly difficult to achieve given the internet’s democratizing effect on knowledge. We are similarly skeptical of analytical advantages. While we certainly believe we’re better-than-average business analysts, we also recognize that the human tendency towards overconfidence is one of the most robust findings in behavioral psychology. Combining this finding with the ever-increasing quality of the competition in investing, we don’t think it’s prudent to base our strategy on achieving a consistent analytical advantage over other investors. What about behavioral advantages? As you’ll see below, we do think these are a source of more enduring investment advantage.

On average, investors are avaricious, impatient, and overconfident. Because investors are avaricious and impatient, they are attracted to wider bell curve, riskier stocks. Because they’re overconfident, they mistakenly believe they can pick the risky stocks with a higher likelihood of positive outcomes. We believe these behavioral tendencies lead investors to pay, on average, too much for these risky stocks, causing a consistent mispricing in the market. On the flip side, we believe investors’ tendency to be too short-term oriented and overly risk-seeking causes them to underappreciate the best, most predictable, most enduring businesses, leading to a consistent underpricing of these businesses. We call this market inefficiency the “high-quality-business mispricing,” and, at YCG, we attempt to exploit this inefficiency by focusing our efforts and capital on what we believe to be enduring businesses with predictable and attractive long-term economics. In the next section, we will examine the framework we use to identify these great businesses.

In order to survive and thrive over the long term, a business must consistently achieve returns above its cost of capital. In our view, the two most important characteristics that enable a business to achieve this goal are 1) enduring pricing power[2] and 2) long-term volume growth opportunities.

While it’s fairly easy to identify businesses that currently exhibit pricing power and volume growth,[3] it’s much more difficult to identify the subset of these businesses that possess enduring pricing power and long-term volume growth. In order to accomplish this task, it’s helpful to step back and think about the way the world works.

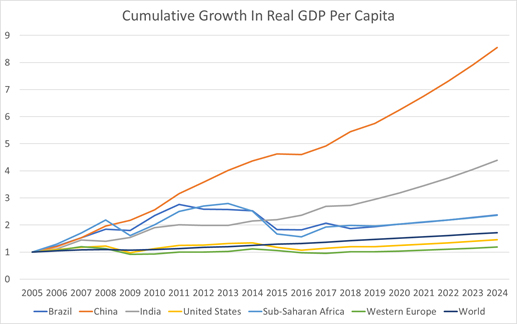

Broadly, the main driver of human progress is innovation, which leads to an unending stream of better, faster, and cheaper ways of doing things. In other words, it leads to abundant wealth creation, as we can see in the following chart.[4]

In this chart, we see rising per capita income occurring in countries across the world. Encouragingly, these income gains are occurring most rapidly in many of the poorest regions of the world as advances in global communication have supercharged their growth by enabling them to more easily adopt many of the richest countries’ best practices while innovating on their own as well.

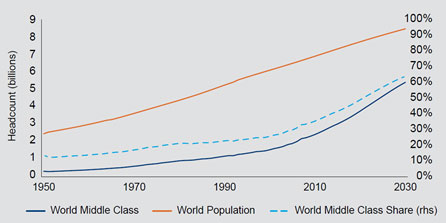

Below,[5] we see that these rising per capita incomes are leading to a large and rapidly growing global middle class.

So far, innovation seems great for almost all businesses. After all, it creates more and wealthier potential customers each passing year. However, innovation turns out to be a double-edged sword for businesses because it also creates rapidly deflationary pricing, which can wreak havoc on a business’s profit potential.

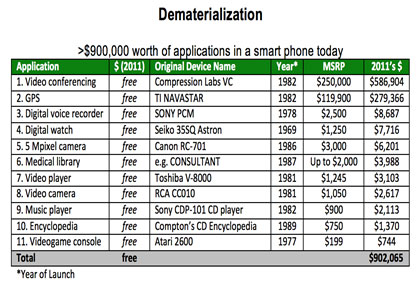

This danger is most clear when looking at technology. We’re all familiar with the rapidly declining prices in this sector, but the exponential nature of these declines leads to jaw-dropping charts such as the one below, which shows that, 30 to 40 years ago, it would have cost almost one million dollars to reproduce only a partial list of the functions available on a $500 smartphone today.[6]

And, believe us, you would not have been able to fit this long list of applications into your pocket back then!

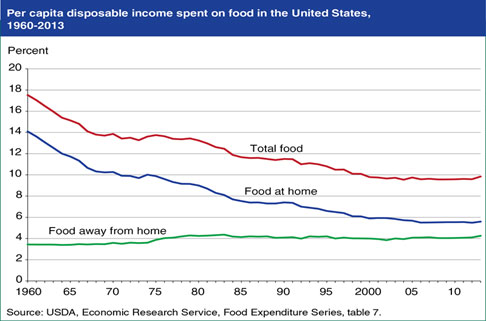

However, these deflationary forces aren’t limited to technology. They are driving down prices in many other large and important sectors as well. For example, food prices are becoming a smaller percentage of our budget. In other words, they are declining in real terms.

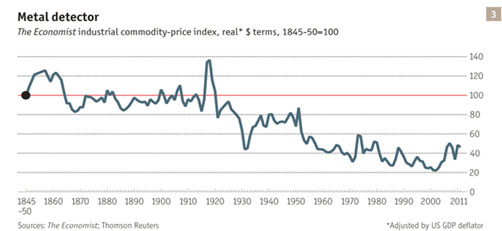

The same is true for industrial commodities. Real prices are going down over time.

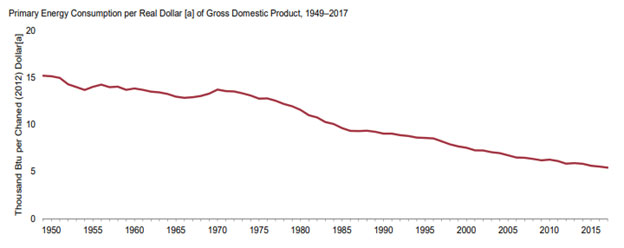

Even energy, the resource that literally powers all the other sectors, is declining in price over time.[7]

So, this analysis begs the question. How does one find businesses with pricing power in a deflationary world? Well, the answer, as any economist will tell you, is to find the scarce good. And, increasingly, the scarce good is . . . time.

Because of innovation, the growth rate of potential experiences, opportunities, and human connections is far outstripping the growth in humanity’s units of attention, causing each unit of our attention to become more valuable over time. As a consequence, goods and services that help us filter through the myriad uses of our attention are also growing in value over time. These are the goods and services in which we seek to invest, and we have found they can be divided into two categories: reliable information filters and reliable people filters.

The first category is reliable information filters. Under our definition, these are filters for safety reliability, efficiency, and personal preference in industries indexed to GDP growth or better. An information filter can maintain or raise prices as long as two conditions are met: 1) the cost of searching for an equivalent substitute must be higher than the savings a customer would achieve by doing so, and 2) the cost of creating an equivalent substitute must be higher than the information filter’s price. While many information filters possess pricing power, not all do, and, even among those that do, there is wide variation in both the current strength and the enduring nature of their pricing power. Thus, we’ve developed a framework that helps us identify what we believe to be the strongest of these information filters. In our view, information filters are more likely to possess robust and enduring pricing power if:

- they are cheap relative to a business’s or person’s income. When a good or service is a small part of someone’s budget, he or she is less likely to find it worthwhile to search for substitutes.

- they provide value well in excess of their price. If a good doesn’t provide at least as much value as its price, then it’s not worth purchasing at all. In the happy scenario where the good provides value well in excess of its price, the consumer believes he or she is getting an attractive deal, and the company selling the product has the ability to raise prices over time to be more in line with the value of the good.

- they benefit from one or more network effects. A network is a group of interconnected people or things (commonly referred to as nodes of the network). Networks have the property that each additional node added to the network creates more value than the cost of adding the node. This result occurs because the value of the network is dependent on both the value of each node and the value of the connections between the nodes. In order to understand this concept, let’s consider the simplest example possible, in which the nodes are people and there is one existing person and then a second person joins the network. In this case, the value of the network increases not just by the value of the second person but also by the value of the connection between the first and second person. Then, when a third person joins, the value of the network increases by one person and two connections. When a fourth person joins, the value increases by one person and three connections. As you can see, the larger the network gets, the more value each additional person provides because of the increased number of connections.

Because of this exponential explosion in value as networks scale, companies that own a large network can charge significant and increasing rates for access to the network while still maintaining a nearly insurmountable competitive advantage over smaller competing networks. Again, a simple illustration helps to clarify the point. Consider a new user choosing between a 1,000-person network and a 50-person network. By joining the larger network, the new user would create the ongoing value of 1,000 new connections. By joining the smaller one, the new user would only create the ongoing value of 50 new connections. However, the new user clearly didn’t create that value on his or her own. Rather, the value was created by both the new user and the people on the other side of each of these new connections (i.e. the existing users of the network). Assume, therefore, that each new user must share half the value of these new connections with the existing users. Even after this sharing of value, the new user is still left with the value of 500 connections if he or she chooses the larger network and the value of only 25 connections if he or she chooses the smaller network. This huge gap in value means that, even if the owner of the larger network charges the new user the value of 200 connections (leaving the value of 300 connections) and the owner of the smaller network pays the new user the value of 125 connections (resulting in the value of 150 connections), it would still be twice as beneficial/profitable for the new user to join the larger network. This astonishing result is why we think network effects are so important to a business’s ability to possess enduring pricing power.

In evaluating the strength of each network effect, we consider:

- the size of the network relative to competing networks: both locally and across geography. While we already thoroughly discussed the value of network size in the discussion above, we think it’s important to highlight that we strongly prefer global networks. In our view, global networks are better because they benefit much more from the rising global middle class and because networks that are only strong regionally are at somewhat greater risk that they’ll experience tough and value destructive competition from other regionally strong networks that are expanding into their territory.

- the scope of the network: across product offerings/use-cases/time. Similar to networks that are only regionally strong, a company that maintains a very narrowly-defined network is always at risk of being disrupted by companies that have network effects in adjacent categories. Thus, a network with multiple and growing product offerings and use-cases is a much more competitively entrenched network. Further, in the case of data networks in which customers are purchasing time series of data, the historical context provided by the oldest information services firms is a unique and extremely-hard-to-replicate advantage.

- they are typically purchased by an agent (employee) acting on behalf of a principal (owner). This trait enhances competitive advantage and pricing power because the incentives of the employee are different from the incentives of the owner. The upside of intelligent risks typically accrues disproportionately to the owners. Thus, employees are more likely to “play it safe” and choose the more well-known and respected brand or network, even if it is the pricier alternative.

- they benefit from regulatory barriers-to-entry. If a good or service has relatively inelastic demand and regulators only allow a few companies to provide the service, then the company selling the product has significant flexibility over the price it charges.

A quick discussion of Moody’s will bring the points above to life. Moody’s sells credit ratings to corporations, governments, and banks so that they can raise debt from the capital markets. The industry in which they participate, debt capital markets, possesses favorable long-term growth prospects. Debt issuance has historically grown at least as fast as GDP, and capital market bond issuance has grown even faster as it has taken share from banking loans. Over the long term, we believe this GDP or better growth is likely to continue. Moody’s serves as a key information filter in this industry. Moody’s charges corporations approximately 7 basis points[8] to rate their bonds yet likely saves them 30 to 50 basis points[9] in annual borrowing costs. Moody’s benefits from both protocol and data network effects. Because crowded information marketplaces are generally quite inefficient, requiring participants to maintain background knowledge on numerous providers and analytical methodologies, industries such as credit ratings tend to coalesce around one or two standards (i.e. protocols). Moody’s and its main competitor, Standard & Poor’s, are the globally-recognized credit rating standards with far larger networks and far more data than any of their competitors. Additionally, the scope of their networks is unmatched. They provide corporate, government, and structured product credit data going back, in some cases, over a hundred years, and they provide analytical support and software that increases the use-cases for the data. Moreover, most corporations and governments, along with most large endowments, pension plans, and sovereign wealth funds, are run by employees instead of owners, further solidifying Moody’s competitive position through the principal-agent problem. Finally, for much of Moody’s history, the U.S. government and its various regulatory bodies made Moody’s and a few other specially-designated rating agencies so important to banks’ bond purchases that it made their ratings almost mandatory for most corporations and governments, which led to Moody’s becoming one of the entrenched, global “languages” in the ratings business today. Given that Moody’s checks all our information filter boxes, it’s no surprise that’s it’s historically exhibited more enduring pricing power than almost all other businesses.

The second category is reliable people filters. And the way we define reliable people filters is that they are goods or services that increase perceived attractiveness, filtering for loyalty to a tribe and status within the tribe, in industries indexed to GDP growth or better. A people filter can maintain or raise its price as long as its social signaling value is equal to or greater than the difference in price between the people filter and unbranded alternatives.

Similar to information filters, we’ve developed a framework to evaluate the strength of goods and services as people filters. While you’ll notice important similarities between the two frameworks, there are also important differences. In our view, people filters are likely to have more robust and enduring pricing power if:

- they are socially consumed. Otherwise, how can other people use them as a filter of tribal loyalty or status?

- they are costly to obtain relative to unbranded alternatives. This is the most notable difference with information filters. The great thing about these types of goods is that, for many of them, there is no end in sight to their pricing power. And the reason is simple. A people filter is only valuable so long as it is costly to obtain. In a world of increasing wealth, if the companies that sell these goods do not continually raise their prices, then they will become less and less costly for other people to obtain, making them less and less valuable as signals of loyalty or status.

- they provide more value than their price. However, unlike information filters, the price and value of people filters are correlated since a higher price sends a stronger signal of loyalty and/or status and a lower price sends a weaker signal. Thus, we believe the luxury goods companies need be cognizant of this relationship and keep price and value relatively close together in most cases. An exception to this rule occurs when luxury goods companies produce limited runs of highly desirable items. For instance, Nike limits supply of many of its most desirable shoes, causing a resale market to develop in which these shoes are sold for multiples of the retail price. These shoes remain costly to obtain, but the cost is paid through the time and energy required to follow the release schedule, research the techniques for acquiring the shoes, and, in some cases, camp out at the store ahead of the release. These limited releases strengthen the brand by broadening the customer base and deepening consumer devotion through numerous behavioral psychology principles such as social proof, scarcity bias, and commitment bias. For similar reasons, luxury brands limit or even prohibit discounting. Discounting weakens a luxury brand by causing consumers to question its popularity and desirability.

- they benefit from one or more network effects. The primary network effect from which people filters benefit is a belief network effect. Similar to gold, the more people who believe Louis Vuitton is valuable as a signifier of wealth, culture, and status, the more valuable it is as this signifier. In evaluating the strength of this belief network effect, we consider:

- the size of the network relative to competing networks: both locally and across geography. On this dimension, people filter networks are a little more nuanced than information filter networks. For information filter networks, each incremental user or consumer of the product strengthens the network effort. For many people filter networks, one must differentiate between the network of believers and the network of users. In the case of believers, people filter networks mostly operate similarly to information filters. Each additional person who believes that Louis Vuitton signifies wealth, culture, and status strengthens Louis Vuitton’s belief network. On the user front, as long as each additional user is generally agreed upon by society as a wealthy, cultured, and high-status individual, then more users strengthens the network. However, too many users or the wrong users can cause the filtering function of the product to break down. Additionally, there are certain products where people value knowing that they and others in their tribe are exclusively “in-the-know,” and, thus, even the belief network can have an upper limit of positive network effects. As with information filters, we vastly prefer brands that have already demonstrated global acceptance as people filters.

- the scope of the network: across product offerings/use-cases/time. For people filters, similar to information filters, we look for brands that are able to travel across category, which makes them less susceptible to competitive entrenchment and shows that the brand transcends any particular product instantiation. Additionally, we prefer brands with storied heritages connected to status that participate in product categories that have universal cultural appeal across time (such as leather goods and jewelry). These aspects significantly enhance the latticework of data people are using to determine their level of belief in the brands as reliable people filters. The heritage aspect is particularly important since new brands can’t go back in time and create a heritage, putting them at a huge disadvantage versus incumbents. Hermes is a great example of these principles in action. The Hermes brand is attached to a variety of disparate product areas, everything from leather goods to fashion and fashion accessories to perfumes to watches, each of which is a large and rapidly growing revenue generator for the company. Moreover, the company has a storied heritage connected to celebrities, royalty, and centers of culture going back to its founding in Paris in 1837.

After winnowing the investment universe down to businesses that we believe sell these enduring information and people filters, we then apply additional constraints that eliminate even more businesses from our consideration. We want each business we own to have:

- a management team that is long-term oriented with interests that are aligned with us. Thus, we prefer businesses with high insider ownership, especially those where a founder, family, or CEO has both a large, controlling stake in the company and a long history of treating minority shareholders fairly.

- a conservative capital structure. Since the future is unpredictable, we want all the businesses we own to be able to survive even a deep recession.

- an attractive valuation. We assess this characteristic by calculating the business’s estimated forward risk-adjusted return and comparing it to our forward risk-adjusted return estimates for other equities that we’re considering as well as to other asset classes such as 30-year Treasury bonds. Additionally, in determining whether a business is attractively priced, we consider qualitative factors, with the most important of these being whether we believe investors are over-discounting temporary macroeconomic or operational issues. We believe this “market-timing mispricing,” about which we have written extensively in past letters, can provide some of the best entry points into great businesses.

Finally, with the businesses that pass all these constraints, we then construct a portfolio that we believe will be robust to the unknown future, diversifying across industry, product category, and macroeconomic sensitivity.

Concluding thoughts

So that’s our investment strategy. In summary, we believe the best way to achieve excess returns without excessive risk is to 1) identify great businesses with enduring pricing power and long-term volume growth opportunities; 2) minimize other long-term business risk factors by partnering with ownership-minded management teams and avoiding companies with aggressive capital structures; 3) avoid overpaying by focusing on the high-quality-business mispricing, by remaining vigilant to market-timing mispricings, and by comparing the forward risk-adjusted rates of returns of our businesses with our investment alternatives; 4) diversify as much as possible among the attractively-priced, great businesses we’ve identified; and, finally, 5) wait. This approach has served us well over the years, and we believe it will continue to do so in the future.

As always, know we’re invested right alongside you, and please let us know if there is anything you need. We are here to help.

YCG, LLC has recently filed its Annual Update to Form ADV. There were no material changes, but we would like to advise you that you may request a copy of the most recent ADV Part 2A, at no charge, by contacting us or by accessing it at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov.

Sincerely,

The YCG Team

Disclaimer: The specific securities identified and discussed should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security nor were they selected based on profitability. Rather, this commentary is presented solely for the purpose of illustrating YCG’s investment approach. These commentaries contain our views and opinions at the time such commentaries were written and are subject to change thereafter. The securities discussed do not necessarily reflect current recommendations nor do they represent an account’s entire portfolio and in the aggregate may represent only a small percentage of an account’s portfolio holdings. A complete list of all securities recommended for the immediately preceding year is available upon request. These commentaries may include “forward looking statements” which may or may not be accurate in the long-term. It should not be assumed that any of the securities transactions or holdings discussed were or will prove to be profitable. S&P stands for Standard & Poor’s. All S&P data is provided “as is.” In no event, shall S&P, its affiliates or any S&P data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the S&P data. MSCI stands for Morgan Stanley Capital International. All MSCI data is provided “as is.” In no event, shall MSCI, its affiliates or any MSCI data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the MSCI data. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

[1] For information on the performance of our separate account composite strategies, please visit www.ycginvestments.com/performance. For information about your specific account performance, please contact us at (512) 505-2347 or email [email protected]. All returns are in USD unless otherwise stated.

[2] Cost advantages can also lead to returns above the cost of capital, but we believe they are less likely to be enduring given humanity’s relentless drive to reduce costs through innovation, leading to new disruptive technologies or materials that leapfrog incumbent cost advantages. For example, Saudi Arabia has a sustainable cost advantage in oil, but new drilling technologies may increase supply faster than demand and/or reduce Saudi Arabia’s cost advantage relative to competitors. Even more existentially threatening, solar energy prices may eventually fall enough to make oil uncompetitive.

[3] One need only run a screen that selects for businesses that produce high returns on both existing and incremental tangible assets, wide and growing margins, and revenue growth.

[4] See https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/WEOWORLD/IND/CHN/BRA/USA/WEQ/SSQ. 2020-2024 are estimates.

[5] See https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/global_20170228_global-middle-class.pdf.

[6] Chart from book Abundance by Peter Diamandis and reproduced in the following article:

[7] See https://www.eia.gov/totalenergy/data/monthly/pdf/sec1_16.pdf.

[8] See https://www.standardandpoors.com/en_US/delegate/getPDF?articleId=2148688&type=COMMENTS&subType=REGULATORY. Given the duopolistic nature of the industry, we believe Standard & Poor’s pricing is a good proxy for Moody’s.

[9] In 2012, for the first time in its history, Heineken decided to get its debt rated. Based on Heineken’s post-mortem analysis, getting its debt rated saved the company 30 to 50 basis points of yearly interest cost. See http://treasurytoday.com/2013/02/do-companies-need-to-be-rated-to-issue-bonds.