The S&P 500 returned -0.76% in the quarter ended March 31, 2018.[1]

In our last letter, we discussed our belief that the best investments benefit from two sources of mispricing: 1) a great business mispricing that we believe results from investors generally undervaluing the rare businesses with both enduring pricing power and long-term volume growth opportunities and 2) a market-timing mispricing that we believe results from most investors’ overconfidence about their ability to enhance their returns by trading around the temporary macroeconomic and operational problems that these great businesses inevitably face over time. Despite its strong recent stock price performance, we believe Moody’s (MCO) continues to suffer from both these mispricings. As a result, we have continued adding to our position in the stock, and it is now one of our largest holdings. In the pages that follow, we will discuss both why we believe Moody’s is a great business and why we believe many investors are erroneously waiting for a better entry point.

Moody’s

Moody’s is the second largest credit rating agency in the world. We believe it is a great business because 1) the business of rating bond issuances has favorable long-term growth tailwinds, 2) the rating agency business model is excellent, 3) an investment in Moody’s is the most focused bet on the rating agency business, and 4) Moody’s management is aligned with shareholders and executing a strategy that we believe is likely to increase business value over time.

The first reason we believe Moody’s is a great business is that the business of rating bond issuances benefits from two long-term growth drivers: rising overall debt issuance and increasing market share of bonds as a percentage of overall debt issuance.

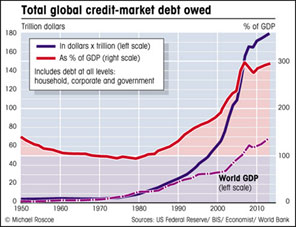

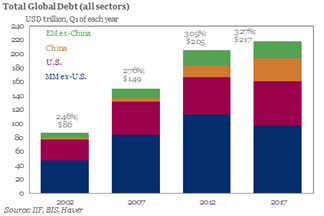

First, we believe debt issuance will rise over time. Because competitive markets drive down the returns on capital of most projects over time, companies and governments are always searching for cost advantages. One clear cost advantage is a lower funding cost. Because investors have varied risk and volatility preferences, companies can generally achieve lower overall funding costs by dividing their capital raisings into a variety of debt and equity instruments that meet these diverse preferences rather than by attempting the one-size-fits-all solution of pure equity. Thus, market pressures will force many companies to raise debt in order to be competitive. Even in uncompetitive markets where companies possess monopolies or oligopolies, investors’ constant focus on maximizing return per unit of risk will pressure companies to add some debt to their capital structure (with the notable exception of family-owned companies that may choose to preference a more risk-averse, and perhaps suboptimal, capital structure). Thus, over the long term, as wealth and global business revenues grow, it seems likely to us that debt issuances will grow as well. This long-term trend of increased debt can be clearly observed in the charts below:

In fact, not only has debt growth kept up with global revenue (GDP) growth, it’s dramatically exceeded it. Both global debt and global GDP began the 1950s at less than $10 trillion, with global debt at only roughly 70% of global GDP. However, by the beginning of 2012, while global GDP had risen sharply to over $67 trillion, global debt had rocketed to an astounding $205 trillion, over 300% of global GDP. Since 2012, the trend of supercharged debt growth has continued, with global debt ending 2017 at $217 trillion, 327% of global GDP.[2]

Does the historical trend of rising debt to GDP mean we should expect debt issuance to continue to grow at faster rates than GDP into the indefinite future? Certainly not into the indefinite future, since there is clearly an upper limit to how much debt global revenues can support. However, the limits of global debt to global GDP are poorly understood. Therefore, it’s perfectly possible that debt grows faster than GDP for years and perhaps even decades to come. After all, Japan’s debt to GDP is above 600 percent,[3] yet the country shows no signs of crisis despite being plagued by a shrinking population, poor corporate governance, and subpar capital allocation. On the other hand, if labor gains more power, interest rates keep rising, and the world becomes more protectionist, it’s also possible that global debt to GDP reverts to a lower level over the coming decades, as it did over the 30-year period from 1950 to 1980.

We tend to favor the view that the greater interconnectedness, higher wealth, and faster technological deflation of today’s world can likely sustain relatively low interest rates and high historical debt-to-GDP ratios, but we remain cognizant of the very real possibility that debt levels could grow more slowly than GDP over the coming decades. Fortunately, Moody’s has a number of other growth drivers that could offset such a scenario, including the second long-term growth driver of bond issuances: share gains.

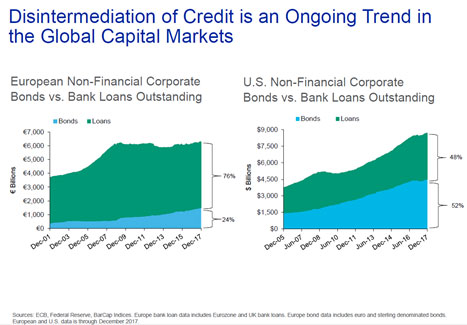

While debt issuances have grown rapidly over time, bond issuances have grown even faster. When market economies are new, banks are generally companies’ main source of financing. However, as these economies mature, capital markets develop in which companies can raise debt through the sale of bonds to investors. Because this source of financing is auction-driven, crowd-sourced, and more global than bank financing, it is generally cheaper, more liquid, and less restrictive. These advantages have enabled bonds to gain significant share over time, as seen in the chart below, and we believe they will continue to take share in the future.

The second reason we believe Moody’s is a great business is that the rating agency business model is excellent. It benefits from three major advantages: deep entrenchment in the functioning of the financial markets, untapped pricing power, and low capital intensity.

The first business model advantage is the rating agencies’ deep entrenchment in the functioning of the financial markets, which makes a seal of approval from Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s (and to a lesser extent, Fitch) almost indispensable to most companies issuing bonds. To understand credit ratings’ importance, a little history is needed.[4]

Starting in the mid-1800s, the United States began to experience a railroad boom. To satisfy the interest in the companies behind this boom, a man named Henry Varnum Poor, the founder of the company that eventually became Standard & Poor’s (“S&P”), began publishing independent financial and operational statistics on the various U.S. railroad companies. Then, in the early 1900s, investor enthusiasm and the railroad companies’ increased financing needs catalyzed a corporate bond market that quickly grew to be several times larger than those in other countries. After the 1907 financial crisis, demand grew for independent credit analysis of these railway bonds. In 1909, John Moody, the founder of the company that would eventually become Moody’s, met this demand with the first widely-accessible publication rating railroad bonds. Later, in 1914, the Fitch Publishing Company was founded. All three companies continued to grow and to become more widely used. Then, in 1936, after the Great Depression, regulation was introduced mandating that U.S. banks could only own bonds if they were designated as investment grade by four legally-endowed ratings agencies, Moody’s, Poor’s, Standard, and Fitch. This regulatory advantage was further enhanced when, in 1975, the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) issued rules around capital requirements based on the ratings of the “Big Three” credit rating agencies (Standard had merged with Poor’s by this time). As a result of these moves, credit ratings became deeply entrenched in the financial system, with virtually all public and private companies as well as individual fixed income investors measuring their risk using these conventions.

However, while the special regulatory designations granted by the government are no doubt important, they are clearly not the only competitive advantage that Moody’s and S&P possess. Despite the government having expanded the list of Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations (“NSRSOs”) from three to ten over the last fifteen years, Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch have experienced neither pricing pressure nor market share erosion, easily maintaining their stranglehold on the credit rating business. This continued dominance shows that the Big Three rating agencies benefit from an additional competitive advantage that is very hard to disrupt. They have become the standard, shared global language of the bond business.

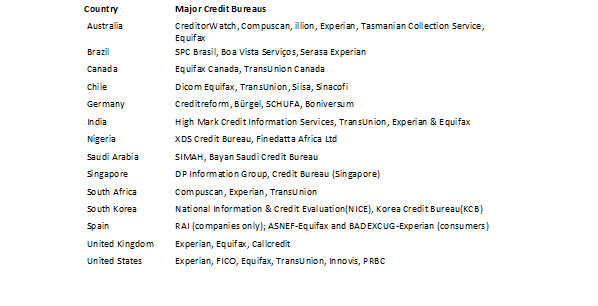

These standards tend to develop because crowded information marketplaces are generally quite inefficient, requiring participants to maintain background knowledge on numerous providers and analytical methodologies. On the other hand, a single provider is subject to few checks and balances, causing market participants to generally support a few competitors. The rating agencies provide a great example of this dynamic. While no company has ever possessed a monopoly on the credit rating business, there have also never been more than four credit rating agencies with significant market share over the industry’s more than one-hundred-year history.[5] Similarly, the consumer credit bureau business usually coalesces around only a few players, with the U.S., for example, being dominated by Equifax, Experian, and Transunion.

Once these winners emerge, they are very hard to disrupt. First, information becomes more valuable the more context it provides. By definition, the longer a company has been collecting data, the more historical context it can provide. Second, familiarity breeds trust, giving a big advantage to companies with dominant market share and storied histories. Third, many industry stakeholders are agents (employees) acting on behalf of principals (owners). These agents generally prefer the easiest and safest decisions because the upside to the agent’s career from a good unconventional choice rarely compensates for the downside to his/her career from a poor one. Thus, from the agent’s perspective, the unconventional choice is not worth the extra effort and risk, especially in cases where the conventional choice is no more expensive. This common principal-agent problem birthed the popular aphorism, “You never get fired for choosing IBM.” Fourth, the standards created by the winning companies generally catalyze the creation of an ecosystem populated by tools designed to improve the usefulness of these standards. This decentralized, embedded ecosystem creates large switching costs that are generally only overcome if a standard is incredibly poorly designed or a paradigm shift occurs. An example of a poorly designed standard is the Dow Jones Industrials Average (“DJIA”), which conveyed almost no useful information [6] and was thus superseded by the S&P Indices (though, amazingly, the DJIA is still widely quoted, even today). An example of a paradigm shift would be the technological leap from VHS to DVD, making the VHS standard essentially worthless over time. Fifth, the more the global the ecosystem, the higher its switching costs.

Applying this framework to the Big Three clarifies the strength of their position. They have all been publishing ratings for over one hundred years, providing unmatched historical context. Not only are their brands universally recognized, but few people could even name a fourth rating agency. Additionally, much of the money in fixed income is invested by agents with little or no personal ownership of the underlying bonds. Many of these agents therefore require a rating from at least two of the Big Three, believing they can blame the rating agencies in the event that the bonds default. Furthermore, the Big Three have strengthened their natural network effects by developing proprietary analytics services and tools that they sell to issuers and investors so that they can better understand the ratings from a current, future, and historical perspective. The tools require investments in training and also enhance the usefulness of the ratings, further increasing market participants’ switching costs. Finally, the ratings agencies are rare, even among data businesses, because they tend towards a global standard. To clarify this point, let’s contrast them with the credit bureaus we discussed earlier. Credit bureaus collect proprietary credit data on individuals and then sell this information to banks, helping them to make better loans. However, most banks focus their efforts domestically both because local knowledge is valuable in lending and because governments’ implicit and explicit bank guarantees result in regulations that dissuade overseas growth. Thus, a U.S. credit bureau’s proprietary data is incredibly useful for a bank doing business in Texas, but it doesn’t really help a Chinese bank decide whether to lend money in Shanghai. The credit bureaus, therefore, have to build their businesses market-by-market and have very little advantage when entering a new country. As the chart below demonstrates, this dynamic has resulted in a variety of country-specific winners in the credit bureau space.[7]

In contrast, because capital markets are global and because most global investors derive more information and comfort from the shared, global language of the Big Three ratings than from that of a less familiar domestic upstart, an Indian company issuing corporate bonds is highly incentivized to purchase ratings from the Big Three. The market for bond ratings, therefore, should be much more likely to have only a few global winners. Thus far, the evidence supports this explanation, with Moody’s and S&P each controlling roughly 40% of the global market and Fitch controlling 15%.[8]

In summary, we believe the rating agencies, and Moody’s and S&P in particular, possess nearly unassailable competitive advantages that make it highly likely their global market share dominance will persist over time.

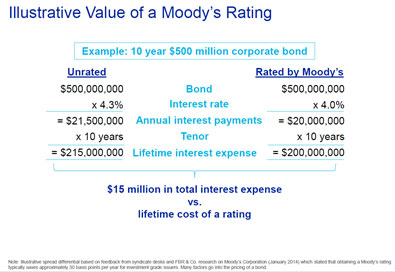

The second business model advantage is the rating agencies’ untapped pricing power. Because ratings are so useful as information filters, they are highly valued by the markets. Moody’s has done an analysis (shown below) that suggests a Moody’s rating saves the average issuer 30 basis points of interest cost per year relative to no rating.

Heineken, a 150-year-old, easy-to-understand beer company corroborates Moody’s management’s claim. In 2012, for the first time in its history, Heineken decided to get its debt rated. Based on Heineken’s post-mortem analysis, getting its debt rated saved the company 30 to 50 basis points of yearly interest cost.[9] Given Heineken’s corporate age, low technological disruption risk, lack of complexity, and conservative family control, this data point suggests that Moody’s conclusion that a rating is worth 30 basis points could be an underestimate.

Nevertheless, even if we use this potentially conservative estimate of 30 basis points, there is still a large gap between the current value of a rating and its current cost. According to S&P’s pricing sheet, which we believe is a good proxy for Moody’s, the current cost of a corporate bond rating is only 6.75 basis points.[10] Since many companies require ratings from two different agencies to achieve the 30-basis-point benefit, let’s double the 6.75 number. Even at 13.5 basis points, the cost-value gap presents a sizeable long-term pricing opportunity. Assuming the value of a rating remains stable over time, Moody’s and S&P could raise their prices by 5% per year for another 16 years before their combined pricing would exceed 30 basis points.

The third and final business model advantage is the rating agencies’ low capital intensity. Since analysts, software developers, and office space are their main expenses, rating agencies are able to return high percentages of their earnings to shareholders even as they grow. Additionally, because employees are such a significant portion of their cost structure, the rating agencies can generally continue to produce cash even in bad downturns since they can pay their people less or downsize. Finally, because of their strong pricing power and steady free cash flow, the rating agencies don’t require leverage to generate attractive returns but can safely support moderate amounts of it.

The third reason that we believe Moody’s is a great business is that we believe an investment in Moody’s is the best bet on the credit rating agency business. As we already discussed, S&P and Moody’s each command roughly 40% of the global bond market, making them the clear leaders. However, an investment in Moody’s is a more focused wager on the credit rating agencies than S&P Global (the parent company of S&P), which gets much of its revenue from its index business. Whereas S&P Global only earned 48% of its 2017 revenue from its rating business and 55% of its operating profits, Moody’s generated 62% of its revenue (pro forma for its recent Bureau van Dijk acquisition) and greater than 80% of its operating profit from this piece. Furthermore, while S&P Global’s index business is fantastic, we believe our longstanding investment in international index provider MSCI, which benefits from the same global network effects that the credit rating agencies do, is even better.

The fourth and final reason we believe Moody’s is a great business is that management’s interests and current strategy are aligned with long-term value creation. With ownership of over $170 million in stock as well as accountability to Berkshire Hathaway (which owns 12.9% of the outstanding shares), we believe Ray McDaniel, Moody’s CEO, is properly incentivized. Let us now turn to McDaniel’s strategic vision and operational accomplishments, dealing first with his role in one of the most ignominious periods of Moody’s history. During the mid-2000s, Moody’s failed miserably in its ratings of mortgage-backed securities, and the misguided triple-A ratings it assigned to many of these bonds clearly exacerbated the housing bubble and the resulting financial panic when the bubble burst. Moreover, McDaniel, who joined Moody’s in 1987 (as an analyst in the Asset Securitization department of all places!) and became CEO in 2005, bears significant responsibility for Moody’s rating failures during this time. However, while this lapse in oversight and judgment was a huge mistake, it doesn’t nullify all of his accomplishments, which are manifold. First, while deserving blame for Moody’s errors leading up to the crisis, McDaniel also deserves credit for successfully navigating the company through its post-crisis turbulence. By bolstering compliance, successfully fighting numerous lawsuits, and settling others when necessary, McDaniel and his team have, as of 2018, largely put this painful period behind them. Additionally, despite these added costs and the loss of much of its high-margin mortgage-backed securities business, Moody’s operating performance under McDaniel has been impressive. Assuming management achieves the midpoint of its 2018 guidance, Moody’s will have grown revenue by 8% per year, reduced diluted shares outstanding by 37%, and increased both earnings and free cash flow per share by 11% per year over McDaniel’s tenure. Additionally, McDaniel has bought numerous tuck-in acquisitions such as Fermat International, ICRA Limited, and Bureau van Dyjk. We believe these acquisitions have strengthened Moody’s credit rating and data analytics offerings, increased switching costs, and enhanced Moody’s growth potential.

Having hopefully convinced you that Moody’s possesses a rare combination of pricing power and growth potential, we can now discuss the temporary issues that we believe are irrationally preventing investors from purchasing the stock. We believe investors are primarily focused on two issues.

First, we believe investors overestimate Moody’s future regulatory, legal, and business risks. We believe the financial crisis was almost a perfect storm for the rating agencies. The agencies mis-rated trillions of dollars of complex, opaque, and untested mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations . . . and not by a little. By 2010, 93% of the triple-A-rated subprime mortgage-backed securities issued in 2006 had been downgraded to junk.[11] Moreover, plaintiffs found numerous emails suggesting that employees at the firms were skeptical of the bonds.[12] Additionally, rating these so-called “structured products” was far more profitable than the historical bread and butter of the agencies, corporate bonds. Thus, this category had grown rapidly, and, at its peak in 2006, was 53% of Moody’s rating revenue. This fact pattern provided a clear motive for plaintiffs’ claims of fraud and negligence. Finally, the agencies’ rating mistakes directly contributed to the worst housing crisis in U.S. history and the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Yet, despite these circumstances, Moody’s has mostly worked through the claims against it, having successfully defended itself or negotiated digestible settlements in all its major legal battles. Moreover, regulatory attempts to hold rating agencies more liable in the future have either not been pursued or have failed due to the agencies’ powerful argument that ratings are opinions protected by the First Amendment.[13] Additionally, as we mentioned earlier, regulators’ attempt to create a more competitive market by adding more agencies to the list of NSRSOs has failed, and Moody’s has been able to grow its revenues by 8% and its earnings per share by 11% since 2005 despite the collapse of the structured finance business (which, as of 2017, was a more reasonable 18% of their ratings revenue). One way to think about the strength of a business is how hard it is to kill, and we believe this period shows that the rating agencies are unusually tough. Thus, our view is that the rating agencies will very likely be fine even if we have a crisis of similar magnitude with similar rating agency culpability. And while neither we nor many investors expect a repeat of this mix of culpability and deep crisis, we do believe that many investors, because of recency and saliency biases, are too pessimistic on both the probability of a near-term deep recession (though one is certainly possible) and the size of the financial penalties the ratings agencies will incur in the next recession. The rating agencies’ bolstered compliance efforts, their more vanilla business mix, and the reduced leverage of the banking system are just some of the changes that are being underappreciated, in our view.

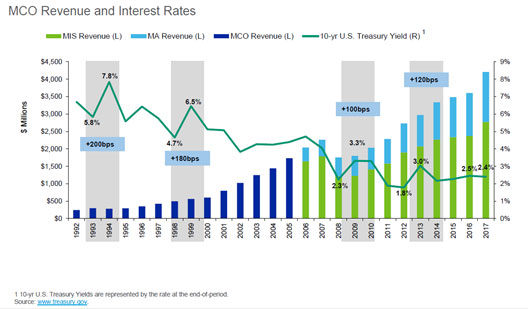

Second, we believe some investors are hesitant to buy the stock because they believe the historically high debt-to-GDP levels that we discussed at the beginning of this letter are unsustainable. These investors believe that central banks have artificially depressed interest rates and that interest rate normalization will depress debt growth, putting pressure on Moody’s revenue over the medium term. We’ve already stated that we tend to favor the view that the world’s interconnectedness and the forces of technological deflation such as the internet, artificial intelligence, and robotics can likely sustain reasonably low interest rates. We would only add that, even if rates do rise somewhat over time, debt issuances may be less pressured than investors currently believe, as the chart below, which shows past periods of rising interest rates, suggests.

While we believe that the macroeconomic-related investor concerns surrounding Moody’s are overdone and that our behavioral analysis is sound, we always like to have valuation evidence that supports our mispricing beliefs as well. In the case of Moody’s, we believe this evidence is strong. During the six years preceding the financial crisis,[14] as a result of its many favorable attributes, Moody’s traded at an average premium to the U.S. stock market of 34%. Even after the recent run-up in the stock, Moody’s currently trades at 20.5x forward earnings versus the market at 16.6x, a premium of only 24%.[15]

In summary, we believe that Moody’s is one of the best businesses in the world, that the market doesn’t fully appreciate this fact, and that this error is compounded by many investors’ belief that they are likely to get a better deal on Moody’s stock at some future point in the macroeconomic cycle.

Concluding thoughts

As our Moody’s analysis hopefully demonstrates, we take our role as stewards of your capital very seriously. We recognize the trust you’ve placed in us, and we endeavor to earn that trust by performing deep analysis on promising investment opportunities, stress-testing our portfolio, diligently servicing your accounts, and periodically updating you on both our thought process and investment selections. Know that we are invested right alongside you and that we are always available if you have any questions or concerns.

Thank you for the opportunity to serve you, and we look forward to communicating again next quarter.

Sincerely,

The YCG Team

Disclaimer: The specific securities identified and discussed should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security nor were they selected based on profitability. Rather, this commentary is presented solely for the purpose of illustrating YCG’s investment approach. These commentaries contain our views and opinions at the time such commentaries were written and are subject to change thereafter. The securities discussed do not necessarily reflect current recommendations nor do they represent an account’s entire portfolio and in the aggregate may represent only a small percentage of an account’s portfolio holdings. These commentaries may include “forward looking statements” which may or may not be accurate in the long-term. It should not be assumed that any of the securities transactions or holdings discussed were or will prove to be profitable. S&P stands for Standard & Poor’s. All S&P data is provided “as is.” In no event, shall S&P, its affiliates or any S&P data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the S&P data. MSCI stands for Morgan Stanley Capital International. All MSCI data is provided “as is.” In no event, shall MSCI, its affiliates or any MSCI data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the MSCI data. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

[1] For information on the performance of our separate account composite strategies, please visit www.ycginvestments.com/performance. For information about your specific account performance, please contact us at (512) 505-2347 or email [email protected].

[2] See https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2017-06-29/global-debt-hits-new-record-high-217-trillion-327-gdp.

[3] See https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-08-30/piMoody’s-s-baz-says-japan-in-a-bind-as-total-debt-tops-600-of-gdp and https://www.google.com/search?q=japan+total+debt+to+gdp&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwit0_Xq4dXaAhUMOawKHRClDY8Q_AUICygC&biw=1920&bih=974#imgrc=6zK1BV4Epp2nrM:.

[4] This section draws heavily from the following sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Credit_rating_agency, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fitch_Ratings, and https://www.reuters.com/article/uscorpbonds-ratings-idUSL2N17U1L4.

[5] See https://books.google.com/books?id=yl0-LkNBsHMC&pg=PA386&dq=credit+rating+agencies+concentration&hl=en#v=onepage&q=credit%20rating%20agencies%20concentration&f=false.

[6] See https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/09/10/the-dow-jones-industrial-average-is-ridiculous/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.982771718fa0.

[7] The chart is adapted from a more comprehensive one at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Credit_bureau.

[8] See https://www.theguardian.com/business/2012/feb/15/credit-ratings-agencies-moodys.

[9] See http://treasurytoday.com/2013/02/do-companies-need-to-be-rated-to-issue-bonds.

[10] See https://www.standardandpoors.com/en_US/delegate/getPDF;jsessionid=D6525BBF7CFBA38FE8F881D9F62B148F?articleId=1976812&type=COMMENTS&subType=REGULATORY.

[11] See https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/26/opinion/26krugman.html.

[12] See http://www.businessinsider.com/sp-credit-rating-employee-admits-a-deal-couldve-been-made-by-cows-and-we-would-rate-it-2010-4.

[13] See https://www.brookings.edu/research/credit-rating-agency-reform-is-incomplete/.

[14] Beginning on September 30, 2000, the date Moody’s spin-off from Dun & Bradstreet was completed and ending December 31, 2006.

[15] The 34% number was calculated using a time-weighted average of the Moody’s market premiums reported by ValueLine, which calculates its premium relative to the 1,700 stocks in its coverage universe. The 24% number was calculated using Moody’s next-twelve-month consensus earnings estimate and the S&P 500, S&P 400, and S&P 600 next-twelve-month earnings estimates (representing a total of 1,500 stocks) published weekly by Yardeni Research; price and earnings data are as of April 22, 2018.