The S&P 500 Index returned 10.56% and the S&P Global Broad Market Index returned 7.79% in the quarter ended March 31, 2024.1

There are three types of advantages in investing: informational, analytical, and behavioral. In much of the investing past, large and well-resourced investors could obtain significant informational advantages. Information was much less widely distributed, so doing customer surveys, talking to management, and acquiring and processing key economic or company reports faster than others enabled industrious investors to get legal and valuable information on which they could profitably trade. Now, with the democratization of information due to 1) the internet; 2) a large and thriving industry of research services performing continuous survey and data work; and 3) the advent of Regulation Fair Disclosure in October 2000 making it illegal for management to disclose material information to large investors before the general public, we believe informational advantages have mostly disappeared.

This leaves two other possible advantages, analytical and behavioral. As discussed in past letters, we have designed our strategy around exploiting what we believe to be the most durable advantage, the behavioral one. Specifically, we believe investors want to get rich quick and are overconfident about their ability to do so, leading them to systematically undervalue the highest quality and most durable businesses and overvalue the most speculative stocks, a phenomenon that has been confirmed by many academic studies.2 Of course, if we believed that exploiting this behavioral bias were the only possible investment advantage, we would simply own a basket of all companies that screen as high quality and call it a day. As you know, we don’t take this approach. Instead, we select a subset of companies from this basket. And the reason for this choice is that we believe our study of business history, capital markets history, and the science of decision-making has enabled us to develop an analytical advantage as well. In the rest of this letter, we’ll describe this analytical advantage in more detail.

The Signal in the Noise

Throughout most of investment history, getting access to adequate, accurate information about potential investments was at least as big a problem as figuring out how to analyze that information. Today, the situation is completely different. We are all overwhelmed by a flood of investment opportunities and information about them. As a result, the main challenge we face today is the problem of signal processing. In other words, in the near infinity of information to which we have access today, how do we identify the signal and mentally discard the noise?

We’ve previously discussed how we identify and attempt to capture the signal in the investment markets, so we’ll keep this section brief. First, based on our study of historical investment drivers, we believe high-quality businesses are likely to outperform the stock market. Second, we think the high-quality businesses that can maintain or increase their future returns on capital are likely to outperform the set of all high-quality businesses (see our Q3 2023 Client Letter3 for a more complete explanation). Third, we believe the high-quality businesses that are likely to achieve these stable-to-increasing returns exhibit the following characteristics: 1) own dominant networks, preferably on a global basis; 2) possess other checks on competing supply such as not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) zoning restrictions, institutional risk aversion, and switching costs; 3) operate in categories that we believe will grow at least as fast as GDP; 4) have conservative balance sheets; 5) are run by ownership-minded management teams; and 6) possess significant untapped pricing power. Last, by assembling a diverse collection of attractively priced businesses with these characteristics, we believe we’ve reduced the idiosyncratic risk inherent in any single company or industry, further increasing the odds that we’ve captured the signal in the markets.

In contrast to our extensive discussions on how we identify the investment signal, we’ve spent very little time describing how we mentally discard the noise. However, this relative paucity of words is not a reflection on the subject’s importance. In fact, perhaps surprisingly, mentally discarding the noise turns out to be almost as critical to a successful investment process as identifying the signal. To understand why, let’s review an ingenious 1973 study4 of horse handicappers by Paul Slovic, a renowned psychologist specializing in human judgment and decision-making. In the study, he and his team compiled eighty-eight pieces of information relevant to horse racing and then asked a group of professional horse handicappers to make predictions on the outcomes of four sets of races after selecting five, ten, twenty, and forty pieces of this information. Importantly, the researchers asked the horse handicappers to predict not only which horses would win but also how accurate these predictions would be.

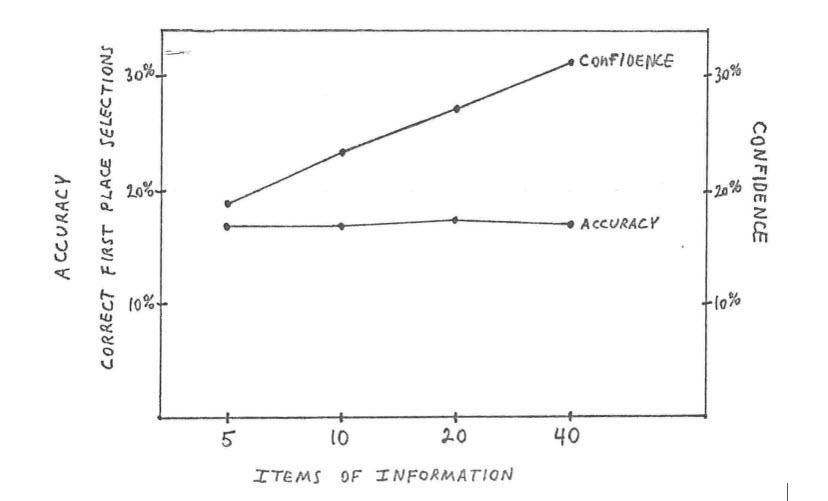

After compiling the results, the researchers began analyzing the data. At first, their findings were unsurprising. When the horse handicappers were allowed to select five pieces of information, they did much better than chance with a 17% success rate compared to the 10% they would have achieved from random guessing, and their confidence in their predictions turned out to be fairly accurate at 19%. So far, so good. As the researchers and horse handicappers had expected, some relevant information was indeed better than no information. Then, however, something strange occurred. When the horse handicappers were allowed to select ten pieces of information, they did no better predicting the outcomes of the races than when they had five pieces of information, remaining stuck at a 17% success rate. Even worse, despite this lack of improvement, the handicappers’ confidence in their predictive ability continued to climb, with the horse handicappers predicting they’d achieve a 25% success rate. Amazingly, this surprising divergence between accuracy and confidence continued in the sets of races where the handicappers had 20 and 40 pieces of information, with their actual success rate remaining static at 17% but their success-rate prediction climbing all the way up to 34%. See the chart below for a visual representation of these results.

Source: Slovic, P. Behavioral Problems of Adhering to a Decision Policy. 1973.

We believe there are three important conclusions to take from this study, the general findings of which have been replicated across other judgment-intensive professions.5

- Horse racing, despite a seemingly limited number of variables, is incredibly hard to predict, with handicappers in this study improving to no better than a 17% success rate. The world, of course, is much more complex than horse racing and, thus, even more difficult to predict. As a result, we should guard against the unknowable by diversifying across a collection of great businesses that operate in different industries and geographies and that are leveraged to various macroeconomic factors.

- There is likely to be little to no advantage to analyzing the tenth or twentieth most important key performance indicator for an investment. We are likely to be far better off focusing our efforts almost exclusively on continuously monitoring and thinking through the top five or so factors that we believe will drive our investment’s success or failure. Therefore, for current and potential investments, we spend all our time analyzing and reanalyzing whether they possess the six “signal” characteristics listed above. Importantly, to avoid confirmation bias, we actively search for errors in our thinking as well as for new information that could change our assessment, such as industry developments that make it easier for new competitors to enter their markets.

- Dividing our efforts between the top ten or twenty most important factors that drive an investment’s success is not just inefficient. It’s also dangerous. As we saw from the horse handicapper study, above a small number of pieces of data, information causes us to have much more confidence in an investment than we should, which can lead to two big problems. The first problem is that overconfidence makes us likely to commit too high a percentage of the portfolio to an investment relative to its actual likelihood of success. The second problem is that overconfidence makes it much harder than it should be to change our minds. Deciding to sell an investment in which we are 80% confident requires much more disconfirming evidence compared to an investment in which we have 40% confidence. And, as we already saw in the study, too much information can indeed cause this level of overconfidence. The handicappers who selected 40 pieces of information were twice as confident as they should have been given their actual success rate.

Conclusion

There are three potential advantages in investing: informational, analytical, and behavioral. As a result of the internet and government regulations, we believe informational advantages have mostly been arbitraged away, leaving analytical and behavioral advantages as the only remaining options. Because we are quite cognizant of how many smart and motivated investment managers are striving for above-average returns, we are hesitant to rely solely on an analytical advantage. Instead, the bedrock of our strategy is to exploit the well-studied phenomenon in which high quality stocks tend to outperform the market and speculative stocks tend to underperform it, which we believe occurs because investors, on average, want to get rich quick and are overconfident about their ability to pick big winners. We try to ensure that we capture the excess returns that result from this behavioral bias by owning a diversified collection of high-quality companies that possess strong profitability and conservative leverage.

However, through our long study of investing, business, and decision-making, we believe we’ve developed an analytical advantage that can enhance these returns further. This analytical approach has two components: identifying the signal and ignoring the noise. In our experience, the most reliable signals of future stock market outperformance are these six business characteristics: 1) ownership of dominant networks, preferably on a global basis; 2) possession of other checks on competing supply such as not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) zoning restrictions, institutional risk aversion, and switching costs; 3) operation in categories that we believe will grow at least as fast as GDP; 4) a conservative balance sheet; 5) an ownership-minded management team; and 6) possession of significant untapped pricing power. Once we’ve assembled a diversified portfolio of attractively priced companies that possess most, if not all, of these characteristics, it’s critical that we then focus our efforts on ignoring the noise. As the horse handicapper study above showed, paying attention to more than a few key performance indicators increases our confidence but not our accuracy, leading to inefficiency and, even worse, overconfidence, both of which are likely to not only increase the risk of the portfolio but also degrade its return.

As always, thank you so much for your trust, know that we continue to be invested right alongside you, and please always reach out to us if you have any questions or concerns. We’re here to help!

Sincerely,

The YCG Team

Disclaimer: The specific securities identified and discussed should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security nor were they selected based on profitability. Rather, this commentary is presented solely for the purpose of illustrating YCG’s investment approach. These commentaries contain our views and opinions at the time such commentaries were written and are subject to change thereafter. The securities discussed do not necessarily reflect current recommendations nor do they represent an account’s entire portfolio and, in the aggregate, may represent only a small percentage of an account’s portfolio holdings. A complete list of all securities recommended for the immediately preceding year is available upon request. These commentaries may include “forward looking statements” which may or may not be accurate in the long-term. It should not be assumed that any of the securities transactions or holdings discussed were or will prove to be profitable. S&P stands for Standard & Poor’s. All S&P data is provided “as is.” In no event, shall S&P, its affiliates or any S&P data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the S&P data. MSCI stands for Morgan Stanley Capital International. All MSCI data is provided “as is.” In no event, shall MSCI, its affiliates or any MSCI data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the MSCI data. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

1 For information on the performance of our separate account composite strategies, please visit www.ycginvestments.com/performance. For information about your specific account performance, please contact us at (512) 505-2347 or email [email protected]. All returns are in USD unless otherwise stated.

2 See https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/2bsymbsfldxbb6unsk268/innovation/deconstructing-high-quality-equity-outperformance and https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-82711-3_10.

3 See https://ycginvestments.com/2023-q3-investment-letter-understanding-return-on-invested-capital/.

4 See https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/23607/928.pdf, pages 53-55 of https://www.cia.gov/resources/csi/static/Pyschology-of-Intelligence-Analysis.pdf, and https://aei.ag/2022/05/31/horse-racing-slovik-information-data-decisions/.

5 See pages 55-57 of https://www.cia.gov/resources/csi/static/Pyschology-of-Intelligence-Analysis.pdf