The S&P 500 Index returned 10.94% and the S&P Global Broad Market Index returned 11.76% in the quarter ended June 30, 2025.1

The second quarter started off with a bang as the Trump administration announced unprecedented tariffs on many countries around the world. This move by the administration created a tremendous amount of geopolitical and investor angst, leading to substantial selloffs in the U.S. stock market, the dollar, and Treasury bonds.2

This sell-off catalyzed the first of our two substantive portfolio moves in the quarter. Since the beginning of the year (and especially since Liberation Day), investors have aggressively sold down Apple’s stock because of their understandable concern about tariff-related increases in manufacturing costs. Conversely, they have bid up Verisk, a firm that is largely immune from tariff risk because it sells mission-critical data to insurance companies. Because we believe Apple’s network effects and pricing power are likely to remain strong over time and because we believe investors tend to overreact to near- and medium-term macro and geopolitical problems (which we call the market-timing mispricing), we used this divergent price action as an opportunity to trim our position in Verisk and add to our position in Apple.

Subsequent to this portfolio change, the Trump administration has softened its stance somewhat and the consumer has remained resilient, leading to a strong market rally that has retraced most of the tariff-announcement-related losses (though not quite as much in Apple’s case, where investors remain worried). Because of the complex-adaptive nature of the economy, with many variables interacting over time to create increasingly surprising knock-on effects, we view the ultimate outcome of both the Trump tariffs and the Apple-Verisk trade as fundamentally unpredictable. However, by 1) owning a diversified collection of global champions with enduring pricing power and long-term volume opportunities and 2) using macroeconomic and geopolitical dislocations as rebalancing opportunities, we believe we’re executing a strategy that can maintain and grow your long-term purchasing power across a wide range of possible scenarios.

The Importance of Unregulated Pricing

Our second substantive portfolio move was to sell our small position in Pepsi, which we believe is facing increased pressure from grocery-store-owned and social-media-driven brand competition as well as from the trend towards healthier eating, which we expect to grow in impact as weight loss drugs’ availability, cost, and effectiveness improve over time. With the proceeds, we bought more FICO, which declined significantly because of comments made by Federal Housing Finance Agency Director Bill Pulte. He expressed displeasure over FICO’s aggressive price increases and suggested that the administration is exploring options to reduce FICO’s monopoly power. These comments, FICO’s price reaction, and our decision to increase the position size serve as a good opportunity to discuss an important part of our investment process that we don’t believe we’ve made explicit in past letters.

First, a quick refresher: As we’ve stated in the past, we believe investors are avaricious, impatient, and overconfident, leading them to, on average, overprice the most speculative stocks and underprice the most high-quality and durable businesses. Furthermore, since competition and innovation eventually drive down the returns of all businesses, investors rationally price these high-quality businesses as though they will experience some long-term erosion to both their inflation-adjusted product pricing and their returns on capital. However, a select few of these businesses can buck this trend and experience constant or rising inflation-adjusted pricing and returns on invested capital over time.

We believe the businesses most likely to accomplish this unlikely feat 1) own a dominant network; 2) possess additional checks on competing supply such as not-in-my-backyard zoning restrictions and institutional risk aversion; 3) operate in a category likely to grow at least as fast as GDP; 4) possess untapped pricing power; 5) have a conservative balance sheet; and 6) are run by an ownership-minded management team. The first four characteristics give the businesses enduring pricing power and the last two characteristics increase the probability that we, as minority shareholders, will benefit from the business value growth that this enduring pricing power is likely to create over time.

This combination of enduring pricing power and strong shareholder protections against bankruptcy and dilution creates what we believe to be a uniquely favorable risk-adjusted return setup. Since investors expect pricing and returns on capital to deteriorate but we believe these businesses have a much higher-than-average probability of maintaining or increasing their prices and returns on invested capital, we believe they are much more likely to surprise investors to the upside than the downside over the long term. Moreover, we believe the magnitude of these upside surprises is likely to be larger, on average, than the downside surprises. In other words, we believe long-term equity ownership of these businesses is positively convex.

However, this analysis makes one key assumption. It assumes that governments will allow our businesses to price for the value they create over time. If they don’t, through mechanisms such as regulation, taxation, or bargaining power, then we believe equity ownership in these businesses is no longer positively convex. Therefore, to own a business, we must believe it’s unlikely governments will cap long-term pricing and returns on capital. The key phrase in this sentence is “long-term.” If history is any guide, we should expect periods of price controls. In the United States, for example, the government instituted price controls in both World Wars and during the early 1970s when inflation began to really accelerate.3 These price controls affected many businesses, including ones with exceptionally enduring pricing power such as Coca-Cola and the aggregates.4 While painful at the time, these temporary periods didn’t prevent the long-term owners of these businesses from experiencing exceptional risk-adjusted returns as the businesses were eventually allowed to price for value.

In contrast, we believe electric utilities, which also possess enduring pricing power because of network effects and increasing demand, are unlikely to be allowed to price for value over time. The importance of electricity costs to consumers, and, therefore, to politicians, has resulted in strict regulatory regimes around the world. For example, in the United States, a state-by-state regulatory regime that first emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries has essentially capped utility company pricing and returns on capital.5 As a result, even though they’re natural monopolies, we think utilities not only lack positive convexity but, instead, exhibit negative convexity. In other words, we think it’s more likely the government decreases their allowed inflation-adjusted pricing and returns on capital over time (a negative surprise) than increases them (a positive surprise). Furthermore, any upside surprise is likely to be muted because of the political importance of electricity prices whereas the downside surprises could be quite severe. One needs to look no further than the United States to see this negative convexity in action. As we write this letter, various entities are suing their states’ utility companies for the damage caused by recent wildfires.6 If they are successful and the utility companies are not allowed to increase prices to incorporate these costs, the owners of these utility companies will earn significantly worse returns on capital than they previously expected. As of this writing, investors are not optimistic, with California’s Pacific Gas and Electric having declared bankruptcy after wildfires in 2017 and 2018, Hawaiian Electric having fallen by over 70% since wildfires in 2023, California’s Edison International having plunged over 40% since wildfires in January 2025, and Warren Buffett declaring that Berkshire Hathaway Energy is “worth considerably less money than it was two years ago based on societal factors.”7

Two other areas that we generally avoid because of similar negative convexity concerns are defense and healthcare. In both cases, the federal government is their largest customer. We think it’s unlikely the federal government will, over the long term, accept price increases that significantly raise the defense and healthcare companies’ inflation-adjusted pricing and returns on capital. In contrast, given most countries’ deteriorating fiscal health and increasingly populist politics, we believe there are many scenarios under which they could decide to decrease them. In healthcare, the situation is arguably even worse than in defense. Healthcare regulations often increase complexity and reduce price transparency, which makes it easier for bad actors to engage in unethical regulatory arbitrage that raises costs for both taxpayers and customers. As a result, it’s very hard to figure out how much of a company’s profits are a result of regulatory arbitrage versus actual value provided to customers on a competitive basis. This opacity, combined with the possibility that the government will change its view on what return on capital it deems fair, explains many of the current woes being experienced by the largest and most dominant U.S. health insurer, United Healthcare. With the stock price having fallen by 40% in a matter of weeks on the back of fraud allegations, cost pressures, and uncertainty over possible changes in regulation, it’s hard to confidently say anything about the return on capital it will earn going forward, except, that is, that it will likely be significantly lower.

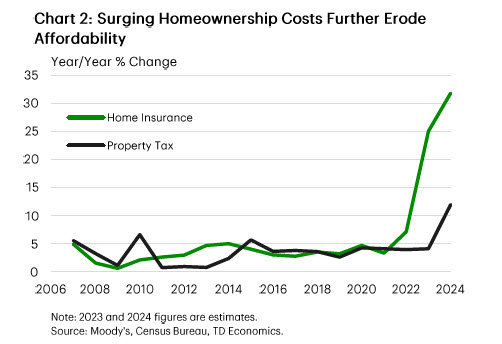

With this context, let’s return to our decision to increase our position in FICO. The government is understandably concerned about housing costs because first-time buyers are facing both a homebuying affordability crisis and a home ownership affordability crisis.8

Against this backdrop, FICO has raised prices in its mortgage division by hundreds of percent over the last seven years. Despite FICO’s reasonable position that it is simply playing catch up after having kept prices constant for the first 30 years of the company’s existence,9 these price increases, combined with FICO’s consumer awareness, have made it a political target. However, we think this focus is misplaced and that regulatory interventions are unlikely to cap FICO’s prices over the long term or displace FICO’s essential role in the U.S. consumer credit ecosystem. Our confidence in this assessment is based on, first, the power of FICO’s network and, second, the large gap between the price the company charges and the value its network creates.

Because crowded information marketplaces are generally quite inefficient, requiring participants to maintain background knowledge on numerous providers and analytical methodologies, industries such as credit ratings tend to coalesce around one or two standards. In U.S. consumer credit, FICO has become this global standard. Furthermore, FICO’s almost 40-year dataset uniquely enables global investors in U.S. consumer credit to contextualize the credit risk they’re taking today compared to the past. Given this powerful value proposition, it’s no wonder that over 95% of the total dollar volume of U.S. consumer credit securitizations solely cited FICO scores as their credit risk measure.10

This dominance is especially understandable when one considers that, despite raising its price per mortgage score by hundreds of percent, FICO still only charges the credit reporting agencies (Equifax, TransUnion, and Experian) $4.95 per score.11 Currently, each credit reporting agency probably pulls the score around one to two times when issuing a mortgage, meaning FICO probably gets paid $15 to $30 per each roughly $320,000 average mortgage loan originated. 12</sup In percentage terms, this price works out to a one-time charge of roughly 0.5 to 0.9 basis points (a basis point is 1/100 of a percent) of the loan balance. In comparison, Moody’s charges around 8 basis points per year to rate corporate issuers’ debt.13 If FICO charged 8 bps per year to mortgage issuers, instead of receiving a one-time payment of $15 to $30, it would receive a payment of $256 in the first year and then a gradually smaller amount in each subsequent year as the mortgages were paid down over time. If you were to present value this stream of cash flows, FICO would receive thousands of dollars of value instead of the $15 to $30 it currently receives.

In Moody’s case, this 8 bps price is an incredible deal for corporate debt issuers because a Moody’s rating likely reduces these issuers’ borrowing costs by 30 to 50 basis points per year.14 While it’s unclear whether FICO’s value in reducing borrowing costs is lower, the same, or higher than Moody’s value, we think it’s quite clear that FICO’s value to mortgage borrowing costs far exceeds the cost of its scores. Therefore, we believe the government will, ultimately, be unsuccessful in its attempt to dislodge FICO’s dominant position in the mortgage ecosystem. In fact, we believe this episode echoes the period after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) when governments around the world were trying to dislodge Moody’s and S&P Global. In that case, Moody’s and S&P Global didn’t merely raise prices by a few dollars. Rather, they made serious ratings mistakes that partially caused the GFC, a crisis that almost destroyed the global financial system and resulted in trillions of dollars in losses for governments and investors. Despite these massive errors, the value of Moody’s and S&P Global’s rating systems as globally shared common languages used to communicate credit risk proved to be so massive that their market positions couldn’t be touched. Fast forward to today (17 years after the GFC), and Moody’s and S&P Global are more dominant and more profitable than ever.

Concluding Thoughts

In a world where economic and geopolitical risks appear to be rising, we continue to be laser focused on owning a diverse collection of global champions with enduring pricing power that we believe can grow in a wide range of future scenarios. Furthermore, we continue to use market volatility to opportunistically rebalance the portfolio, taking advantage of investors’ tendency to overweight short- and medium-term macroeconomic and geopolitical turmoil and underweight long-term pricing power and volume growth opportunities.

Lastly, we wanted to highlight in this letter that an extremely key component of the global champions we own is that they continue to maintain unregulated or lightly regulated pricing. The reason for this emphasis is that a big driver of great stock price performance over time is the ability to positively surprise on pricing, profits, and returns on invested capital. More specifically, we believe the stocks we own need to possess positive convexity. In other words, we want positive surprises to be more probable than negative ones, and we want the magnitude of the possible positive surprises to be larger than the magnitude of the possible negative ones.

We believe growing networks with unregulated or lightly regulated pricing are highly likely to be positively convex over the long term. On the other hand, we believe networks, even growing ones, with explicitly or implicitly capped pricing and returns on invested capital are more likely to be negatively convex. An example of explicitly capped pricing and returns on capital is the utility industry, where strict regulation of these metrics has been in place for many decades.15 Examples of implicitly capped pricing and returns on capital are defense and healthcare, where we believe customer concentration (the government in both cases), declining government fiscal health, and rising populism likely cap long-term pricing and returns on capital.

In conclusion, we believe our job is to try and construct a portfolio that is both positively convex and risk controlled. We believe our filters for enduring pricing power enable our portfolio to exhibit significant positive convexity. We believe our diversification and our focus on high-quality, conservatively capitalized businesses enable us to survive the inevitability that we will sometimes be wrong in our assessment of our investments’ positive convexity. Taken together, we believe these characteristics make it highly likely your portfolio will be able to maintain and grow your purchasing power over time.

As always, thank you so much for your trust, know that we continue to be invested right alongside you, and please always reach out to us if you have any questions or concerns. We’re here to help!

Sincerely,

The YCG Team

Disclaimer: The specific securities identified and discussed should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security, nor were they selected based on profitability. Nothing said in this piece may be considered to be an offer to buy or sell any security. Rather, this commentary is presented solely for the purpose of illustrating YCG’s investment approach. These commentaries contain our views and opinions at the time such commentaries were written and are subject to change thereafter. The securities discussed do not represent an account’s entire portfolio and in the aggregate, may represent only a small percentage of an account’s portfolio holdings. These commentaries may include “forward looking statements” which may or may not be accurate in the long-term. It should not be assumed that any of the securities transactions or holdings discussed were or will prove to be profitable. Data presented was obtained from sources deemed to be reliable, but no guarantee is made as to its accuracy. S&P stands for Standard & Poor’s. All S&P data is provided “as is”. In no event, shall S&P, its affiliates or any S&P data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the S&P data. No further distribution or dissemination of the S&P data is permitted without S&P’s prior express written consent. All MSCI data is provided “as is.” In no event, shall MSCI, its affiliates or any MSCI data provider have any liability of any kind in connection with the MSCI data. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

1 For information on the performance of our separate account composite strategies, please visit www.ycginvestments.com/performance. For information about your specific account performance, please contact us at (512) 505-2347 or email [email protected]. All returns are in USD unless otherwise stated.

2 See https://ycginvestments.com/ycg_perspective/tariff-turbulence-market-update/ for the market update we published after the tariff announcement.

3 See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Price_controls.

4 See https://city-countyobserver.com/449255-2/#:~:text=The%20historical%20record%20suggests%20that,for%20more%20severe%20economic%20problems, https://reason.com/2022/10/13/inflation-remixed/, and https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/FR-1946-03-22.

5 See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rate-of-return_regulation#:~:text=The%20goal%20of%20rate%2Dof,of%20return%20on%20its%20investment.

6 See https://www.carriermanagement.com/news/2024/03/01/259318.htm.

7 See https://www.businessinsider.com/warren-buffett-stock-market-warning-defensive-utility-stocks-berkshire-hathaway-2025-5#:~:text=Warren%20Buffett%20has%20warned%20that,years%20ago%2C%22%20Buffett%20said.

8 See https://economics.td.com/us-housing-market-affordability.

9 See https://www.fico.com/blogs/ficos-adoption-and-pricing-mortgage-origination-market.

10 See page 5 of FICO’s May 2024 IR Presentation at https://investors.fico.com/static-files/f21ffc46-94d2-4a90-80ea-9b40f5e0e6cf.

11 See https://www.fico.com/blogs/fico-s-royalty-pricing-role-and-adoption-mortgage-industry.

12 The average loan amount for all first mortgages originated in December 2023 was $319,531. See page 49 of Equifax’s March 2024 U.S. National Consumer Credit Trends Report – Originations at https://www.equifax.com/resource/-/asset/consumer-report/monthly-us-national-consumer-credit-trends-report-march-2024-originations.

13 See https://www.morningstar.com/company-reports/1221775-moodys-wide-moat-and-profits-revolve-around-its-ratings-business?listing=0P000003P7 and https://web.archive.org/web/20191031183406/https:/www.standardandpoors.com/en_US/delegate/getPDF?articleId=2148688&type=COMMENTS&subType=REGULATORY.

[14] In 2012, for the first time in its history, Heineken decided to get its debt rated. Based on Heineken’s post-mortem analysis, getting its debt rated saved the company 30 to 50 basis points of yearly interest cost. See https://web.archive.org/web/20170812220336/http:/treasurytoday.com/2013/02/do-companies-need-to-be-rated-to-issue-bonds. Also, see https://www.morningstar.com/company-reports/1221775-moodys-wide-moat-and-profits-revolve-around-its-ratings-business?listing=0P000003P7.

[15] See https://www.aer.gov.au/industry/registers/resources/reviews/international-regulatory-approaches-rate-return-pathway-rate-return-2022.